SIDS Prevention

What are the recommended SIDS prevention strategies?

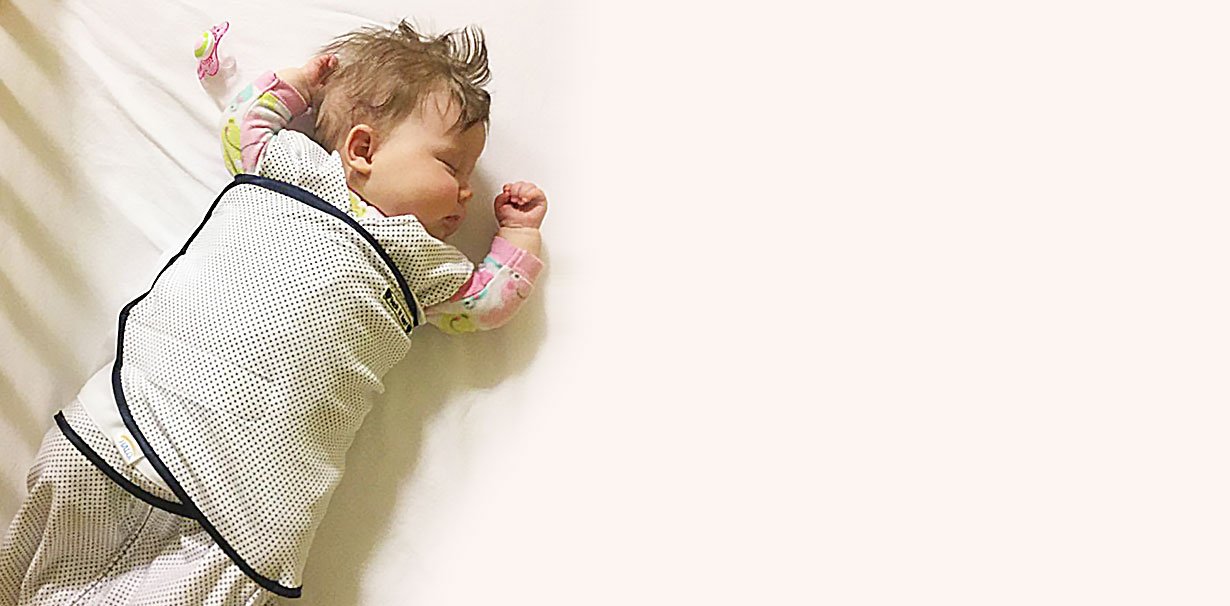

Back to Sleep, Every Sleep

Sleeping on the back every single time is the #1 recommendation to reduce the risk fo sleep-related infant death. Even babies with Reflux. Even babies born premature. Even for naps. Sleeping on the stomach or on the side increases the risk of death.

-

Sleeping on the side or stomach (not recommended) can increase the risk of rebreathing exhaled gas, resulting in decreasing oxygen level and increased carbon dioxide level.

Sleeping on the stomach (not recommended) can also increase the risk of overheating.

Sleeping on the stomach (not recommended) alters the nervous system control of the cardiovascular system which may result in decreased oxygen delivery to the brain.

Sleeping on the back also has an advantage when it comes to choking and spit up. When a baby is on his/her back the tube to the stomach is below the tube to the lungs. If a baby were to spit up, the spit up would have to work against gravity to get into the lungs. When a baby is on his/her stomach, spit up can flow more easily into the lungs, making it easier for the baby to aspirate or choke. Watch this video to explain more.

The risk for SIDS increases more than 2x when a baby is placed to sleep on the stomach or side (both not recommended).

-

Rolling: once a baby can roll, they often will chose to sleep in another position. If a baby can roll both front to back and back to front, while we still recommend placing an infant on the back, if they roll to another position, they can remain- but be very cautious to keep the sleep space clear of any objects that your baby could roll onto. If they can only roll from back to stomach then I often recommend repositioning them onto their back during sleep until they learn to roll back onto their back. Increased tummy time during the day will to help them learn this skill.

Deep sleep: Some adults perceive that their baby looks uncomfortable when sleeping on the back or does not sleep as deeply. Remember, that it is normal for an infant to wake frequently. Studies have shown that infants are less likely to arouse from sleep when sleeping on the stomach (not recommended) and this arousal is a critical protective response during sleep.

Reflux/Choking: Studies from multiple countries have shown no increase in choking since changing to back-to-sleep. The American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (Reflux experts) recommend no position other than sleeping on the back for infants with reflux because of the risk of death. Positioners/wedges/head positioners additionally are not recommended, even for infants with reflux.

-

Kanetake J, Aoki Y, Funayama M. Evaluation of rebreathing potential on bedding for infant use. Pediatr Int. 2003;45(3):284–289

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Kemp JS, Thach BT. Quantifying the potential of infant bedding to limit CO2 dispersal and factors affecting rebreathing in bedding. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78(2):740–745

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Kemp JS, Livne M, White DK, Arfken CL. Softness and potential to cause rebreathing: differences in bedding used by infants at high and low risk for sudden infant death syndrome. J Pediatr. 1998;132(2):234–239

Google ScholarCrossref PubMed

Patel AL, Harris K, Thach BT. Inspired CO(2) and O(2) in sleeping infants rebreathing from bedding: relevance for sudden infant death syndrome. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91(6):2537–2545

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Tuffnell CS, Petersen SA, Wailoo MP. Prone sleeping infants have a reduced ability to lose heat. Early Hum Dev. 1995;43(2):109–116

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Ammari A, Schulze KF, Ohira-Kist K, et al. Effects of body position on thermal, cardiorespiratory and metabolic activity in low birth weight infants. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85(8):497–501

Google Schola rCrossref PubMed

Kahn A, Groswasser J, Sottiaux M, Rebuffat E, Franco P, Dramaix M. Prone or supine body position and sleep characteristics in infants. Pediatrics. 1993;91(6):1112–1115

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Bhat RY, Hannam S, Pressler R, Rafferty GF, Peacock JL, Greenough A. Effect of prone and supine position on sleep, apneas, and arousal in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):101–107

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Ariagno RL, van Liempt S, Mirmiran M. Fewer spontaneous arousals during prone sleep in preterm infants at 1 and 3 months corrected age. J Perinatol. 2006;26(5):306–312

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Franco P, Groswasser J, Sottiaux M, Broadfield E, Kahn A. Decreased cardiac responses to auditory stimulation during prone sleep. Pediatrics. 1996; 97(2):174–178

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Galland BC, Reeves G, Taylor BJ, Bolton DP. Sleep position, autonomic function, and arousal. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1998;78(3):F189–F194

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Galland BC, Hayman RM, Taylor BJ, Bolton DP, Sayers RM, Williams SM. Factors affecting heart rate variability and heart rate responses to tilting in infants aged 1 and 3 months. Pediatr Res. 2000;48(3):360–368

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Horne RS, Ferens D, Watts AM, et al. The prone sleeping position impairs arousability in term infants. J Pediatr. 2001;138(6):811–816

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Horne RS, Bandopadhayay P, Vitkovic J, Cranage SM, Adamson TM. Effects of age and sleeping position on arousal from sleep in preterm infants. Sleep. 2002;25(7):746–750

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Kato I, Scaillet S, Groswasser J, et al. Spontaneous arousability in prone and supine position in healthy infants. Sleep. 2006;29(6):785–790

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Kato I, Scaillet S, Groswasser J, et al. Spontaneous arousability in prone and supine position in healthy infants. Sleep. 2006;29(6):785–790

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Phillipson EA, Sullivan CE. Arousal: the forgotten response to respiratory stimuli. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118(5):807–809

Google Scholar PubMed

Kahn A, Groswasser J, Rebuffat E, et al. Sleep and cardiorespiratory characteristics of infant victims of sudden death: a prospective case-control study. Sleep. 1992;15(4):287–292

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Schechtman VL, Harper RM, Wilson AJ, Southall DP. Sleep state organization in normal infants and victims of the sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics. 1992;89(5 Pt 1):865–870

Google Scholar PubMed

Harper RM. State-related physiological changes and risk for the sudden infant death syndrome. Aust Paediatr J. 1986;22(Suppl 1):55–58

Google Scholar PubMed

Kato I, Franco P, Groswasser J, et al. Incomplete arousal processes in infants who were victims of sudden death. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(11):1298–1303

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Use a Firm and Flat (Non-inclined) Sleep Surface

A firm and flat surface is safest for infants. A firm surface maintains its shape without indenting when the infant is placed on the back. It does not change shape when the fitted sheet is used.

-

Description text Soft mattresses can create a pocket and increase the chance of rebreathing air or suffocation. Memory foam or adjustable fitness mattresses are common in adult bedding, but not safe for infants. Mattress toppers, baby pods, wedges, nursing pillows, cushions, baby head shapers, bean bags, positioners and rolled up blankets are all unsafe.

Infants on an inclined surface (not recommended) are more able to move to their side or belly, and babies on an incline have high energy and strength requirements to maintain safe posture and prevent suffocation. Unfortunately, inclines place the infant at a higher risk of airway obstruction and suffocation. Sleep surfaces with inclines >10 degrees are unsafe for infant sleep. If a baby falls asleep on an inclined surface or sitting device such as a swing, carseat or sling, move them to a safe sleep surface as soon as possible and practical. goes here

-

What exactly is a safety approved crib? It must meet the safety standards of the CPSC, have a firm mattress that fits snugly, have no drop sides, and have appropriate slat spacing. New cribs are recommended as used cribs may no longer meet current safety standards. Bassinets and play yards that meet the safety standards of the CPSC are also safe options. Ensure that the mattress is firm and flat, maintains its shape when the fitted sheet is applied, does not have gaps between the mattress and the walls of the crib/bassinet/play yard. Only use the mattress designed for the specific product and do not substitute.

Checking CPSC: How do we know if a crib or bassinet that meets the CPSC standards? They have a website at CPSC.gov. Unfortunately, I haven’t found a way to look up cribs/bassinets at this website, so I reached out to them. The mail response I received From CSPC Hotline is here: “The manufacturer or importer must provide a Children's Product Certificate (CPC) that certifies that the children's product complies with all applicable children's product safety rules ( or similar rules, bans standards or regulations under any law enforced by the Commission for that product.) The certificate must be provided to the retailers. You can contact the manufacturer of the product for the information. The standards that applies to cribs is 16 CFR 1219.1, 1219.2 and 1220. For bassinets, it is 16 CFR Part 1218.” (Email received 12/28/2017)

Update - New rule! In June, 2021, the CPSC passed a rule that any sleep products for infants <6 months must meet the safety standards of the CPSC if they display any packaging, marketing or instructions indicating that the product is for sleep or naps or have any images of sleeping infants. I whole-heartedly support this rule and hope that it is enforced, but for all my savvy readers, for now, please still ask the manufacturer or importer for the CPC certificate.

-

Description teKanetake J, Aoki Y, Funayama M. Evaluation of rebreathing potential on bedding for infant use. Pediatr Int. 2003;45(3):284–289

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Kemp JS, Thach BT. Quantifying the potential of infant bedding to limit CO2 dispersal and factors affecting rebreathing in bedding. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78(2):740–745

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Kemp JS, Livne M, White DK, Arfken CL. Softness and potential to cause rebreathing: differences in bedding used by infants at high and low risk for sudden infant death syndrome. J Pediatr. 1998;132(2):234–239

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Patel AL, Harris K, Thach BT. Inspired CO(2) and O(2) in sleeping infants rebreathing from bedding: relevance for sudden infant death syndrome. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91(6):2537–2545

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Tuffnell CS, Petersen SA, Wailoo MP. Prone sleeping infants have a reduced ability to lose heat. Early Hum Dev. 1995;43(2):109–116

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Ammari A, Schulze KF, Ohira-Kist K, et al. Effects of body position on thermal, cardiorespiratory and metabolic activity in low birth weight infants. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85(8):497–501

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Kahn A, Groswasser J, Sottiaux M, Rebuffat E, Franco P, Dramaix M. Prone or supine body position and sleep characteristics in infants. Pediatrics. 1993;91(6):1112–1115

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Bhat RY, Hannam S, Pressler R, Rafferty GF, Peacock JL, Greenough A. Effect of prone and supine position on sleep, apneas, and arousal in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):101–107

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Ariagno RL, van Liempt S, Mirmiran M. Fewer spontaneous arousals during prone sleep in preterm infants at 1 and 3 months corrected age. J Perinatol. 2006;26(5):306–312

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Franco P, Groswasser J, Sottiaux M, Broadfield E, Kahn A. Decreased cardiac responses to auditory stimulation during prone sleep. Pediatrics. 1996; 97(2):174–178

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Galland BC, Reeves G, Taylor BJ, Bolton DP. Sleep position, autonomic function, and arousal. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1998;78(3):F189–F194

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Galland BC, Hayman RM, Taylor BJ, Bolton DP, Sayers RM, Williams SM. Factors affecting heart rate variability and heart rate responses to tilting in infants aged 1 and 3 months. Pediatr Res. 2000;48(3):360–368

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Horne RS, Ferens D, Watts AM, et al. The prone sleeping position impairs arousability in term infants. J Pediatr. 2001;138(6):811–816

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Horne RS, Bandopadhayay P, Vitkovic J, Cranage SM, Adamson TM. Effects of age and sleeping position on arousal from sleep in preterm infants. Sleep. 2002;25(7):746–750

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Kato I, Scaillet S, Groswasser J, et al. Spontaneous arousability in prone and supine position in healthy infants. Sleep. 2006;29(6):785–790

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Phillipson EA, Sullivan CE. Arousal: the forgotten response to respiratory stimuli. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118(5):807–809

Google Scholar PubMed

Kahn A, Groswasser J, Rebuffat E, et al. Sleep and cardiorespiratory characteristics of infant victims of sudden death: a prospective case-control study. Sleep. 1992;15(4):287–292

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Schechtman VL, Harper RM, Wilson AJ, Southall DP. Sleep state organization in normal infants and victims of the sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics. 1992;89(5 Pt 1):865–870

Google Scholar PubMed

Harper RM. State-related physiological changes and risk for the sudden infant death syndrome. Aust Paediatr J. 1986;22(Suppl 1):55–58

Google Scholar PubMed

Kato I, Franco P, Groswasser J, et al. Incomplete arousal processes in infants who were victims of sudden death. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(11):1298–1303

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Mannen EM, Carroll J, Bumpass DB, et al. Biomechanical Analysis of Inclined Sleep Products. Little Rock, AR: University of Arkansas; 2019

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Final Rule: Safety Standard for Infant Sleep Products. Washington, DC: Federal Register; 2021

xt goes here

Feed Human Milk

Breastfeeding is associated with a decreased risk of death. Unless a parent is unable to breastfeed, feeding breastmilk exclusively for 6 months and in combination with other foods for 1+ year is recommended to decrease the risk of death.

-

Infant sleep studies showed that breastfed infants are more easily aroused from sleep than formula-fed babies.

Breastfeeding protects against diarrhea and respiratory infections (both of which are associated with an increased risk of SIDS).

Breastfeeding supports a healthy microbiome that may be related to protection against SIDS.

-

Sure, the risk reduction effect of human milk increases with exclusivity, but any human milk feeding is more protective against SIDS than none. Every mother deserves help with breastfeeding, because it can be challenging, particularly at the beginning. If you are struggling with breastfeeding, please reach out to your pediatrician, lactation consultant, or reputable online resources such as KellyMom or La Leche League or Dr. Milk

-

Franco P, Scaillet S, Wermenbol V, Valente F, Groswasser J, Kahn A. The influence of a pacifier on infants’ arousals from sleep. J Pediatr. 2000;136(6):775–779

Google Scholar PubMed

Horne RS, Parslow PM, Ferens D, Watts AM, Adamson TM. Comparison of evoked arousability in breast and formula fed infants. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(1):22–25

Google Scholar PubMed

Highet AR, Berry AM, Bettelheim KA, Goldwater PN. Gut microbiome in sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) differs from that in healthy comparison babies and offers an explanation for the risk factor of prone position. Int J Med Microbiol. 2014;304(5–6):735–741

Google Scholar PubMed

Sleep in Crib in the Parent’s Room.

It is recommended that infants sleep in the parents’ room, close to the parents’ bed, but on a separate surface designed for infants, ideally for the first year of life, but at least for the first 6 months. This decreases the risk of death by about 50%.

-

Why room share?: While we don’t have a definitive answer as to why room sharing decreases the rate of death, we theorize that there are two main reasons room sharing promotes safe sleep. One. The parents are more aware of the infants well being and able to respond quickly if needed. Parents are more easily aroused from sleep when their infant shares a room. Infant monitors do not seem to provide the same protection. Second, the baby is more easily aroused from sleep- they may sleep lighter due to the noises the parents make during their own sleep.

Why not share a bed?: Some studies have found beneficial effects of bed sharing (not recommended). These include improved self-regulation behavior and less negativity at 6 months, but studies also show no differences in infant-mother attachment, infant behavior, and bonding at 18 months. Some breastfeeding groups promote bed sharing (not recommended) to facilitate breastfeeding. However, unfortunately, data consistently show an increased risk for death with bedsharing. Bed sharing is associated with soft bedding, head covering of infants (often accidental) and overall, almost triple the rate of SIDS. Many of the babies who die while bed-sharing are found with bedding covering their face or head

-

Tight spaces: We were unable fit a crib in our bedroom. We used a bassinet until the baby turned 4 months of age, and then changed into a travel crib/play yard in our bedroom, and then moved into the crib in a separate room at age 1

If you accidentally fall asleep: Some people set alarms or turn on TVs/radios to keep from falling asleep while feeding the baby. If you accidentally fall asleep while feeding your baby, return your baby to their crib/bassinet as soon as you become aware. Also, sofas and armchairs are exceptionally hazardous sleep locations for babies, if a caregiver is feeling at risk for falling asleep, falling asleep in an adult bed would be safer than a sofa or armchair.

-

Mao A, Burnham MM, Goodlin-Jones BL, Gaylor EE, Anders TF. A comparison of the sleep-wake patterns of cosleeping and solitary-sleeping infants. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2004;35(2):95–105

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Volkovich E, Ben-Zion H, Karny D, Meiri G, Tikotzky L. Sleep patterns of co-sleeping and solitary sleeping infants and mothers: a longitudinal study. Sleep Med. 2015;16(11):1305–1312

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Bilgin A, Wolke D. Bed-sharing in the first 6 months: associations with infant-mother attachment, infant attention, maternal bonding, and sensitivity at 18 months. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2021;43(1):e9–e19

Google Scholar Crossref

Vennemann MM, Hense HW, Bajanowski T, et al. Bed sharing and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome: can we resolve the debate? J Pediatr. 2012;160(1):44–8.e2

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Hauck FR, Herman SM, Donovan M, et al. Sleep environment and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in an urban population: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 2):1207–1214

Google ScholarPubMed

Blair PS, Fleming PJ, Smith IJ, et al. Babies sleeping with parents: case-control study of factors influencing the risk of the sudden infant death syndrome. CESDI SUDI research group. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1457–1461

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Bacon C, et al. Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths Regional Coordinators and Researchers. Environment of infants during sleep and risk of the sudden infant death syndrome: results of 1993–1995 case-control study for confidential inquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy. BMJ. 1996;313(7051):191–195

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Tappin D, Ecob R, Brooke H. Bed sharing, room sharing, and sudden infant death syndrome in Scotland: a case-control study. J Pediatr. 2005;147(1): 32–37

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

McGarvey C, McDonnell M, Chong A, O’Regan M, Matthews T. Factors relating to the infant’s last sleep environment in sudden infant death syndrome in the Republic of Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(12):1058–1064

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Blair PS, Mitchell EA, Heckstall-Smith EM, Fleming PJ. Head covering – a major modifiable risk factor for sudden infant death syndrome: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(9):778–783

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Keep Crib Clear of Soft Objects

Keep pillows, toys, quilts, comforters, stuffed animals, mattress toppers, mats, burp cloths, sleep docs/pods, bedding (aside from fitted sheets), lovies, bean bags, positioners, rolled up blankets, BUMPERS, head shapers, cords, and other objects away from the sleep area.

-

Objects in or near the crib can cause suffocation, entrapment, wedging and strangulation. Loose bedding can obstruct an infant’s nose and mouth. Soft objects and loose bedding are the most common cause for accidental infant suffocation. Avoid weighted blankets and weighted sleepers.

-

Watch out for cords from baby monitors and blinds/shades which a baby can reach for and become fatally entrapped. Keep toys and other soft items out of the sleep environment. There are no safe bumpers. Tragically, babies get strangled by bumpers. Bumpers can suffocate babies. Even the cute ones. Even the mesh ones. Don’t attach anything to the crib, and don’t put anything in the crib except the baby (and possibly a pacifier, see below).

If in doubt, keep it out!

-

Gaw CE, Chounthirath T, Midgett J, Quinlan K, Smith GA. Types of objects in the sleep environment associated with infant suffocation and strangulation. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(8): 893–901

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Erck Lambert AB, Parks SE, Cottengim C, Faulkner M, Hauck FR, Shapiro-Mendoza CK. Sleep-related infant suffocation deaths attributable to soft bedding, overlay, and wedging. Pediatrics. 2019;143(5):e20183408

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Thach BT, Rutherford GW Jr, Harris K. Deaths and injuries attributed to infant crib bumper pads. J Pediatr. 2007;151(3):271–274, 274.e1–274.e3

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Scheers NJ, Woodard DW, Thach BT. Crib bumpers continue to cause infant deaths: a need for a new preventive approach. J Pediatr. 2016;169:93–7.e1

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Offer a Pacifier

Offering a pacifier for sleep is recommended to reduce the risk of sleep-related death.

-

We are not totally sure why pacifiers decrease the risk of death, but studies consistently show that they do - even if the pacifier falls out. Theories range from improved airway opening during sleep, improved arousal, and favorable modification of the nervous system during sleep.

What about thumb/finger sucking?: The jury is still out - one study showed a decreased risk for SIDS in thumb-sucking, but not as protective as pacifiers. Another study showed no change in risk.

-

Pacifier use can interfere with breastfeeding, so pediatricians generally recommend waiting until breastfeeding is well established prior to using a pacifier. Well established means, a comfortable and consistent latch, adequate milk supply and good infant weight gain.

There is no need to replace a pacifier if it falls out - the protection seems to persist. Also, some babies refuse a pacifier - do not force a baby to take an unwanted pacifier.

Do not attempt to attach the pacifier to your baby, or use a pacifier that is attached to strings or stuffed animals.

-

Hauck FR, Herman SM, Donovan M, et al. Sleep environment and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in an urban population: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 2):1207–1214

Google Scholar PubMed

Carpenter RG, Irgens LM, Blair PS, et al. Sudden unexplained infant death in 20 regions in Europe: case control study. Lancet. 2004;363(9404):185–191

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

McGarvey C, McDonnell M, Chong A, O’Regan M, Matthews T. Factors relating to the infant’s last sleep environment in sudden infant death syndrome in the Republic of Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(12):1058–1064

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Tappin D, Brooke H, Ecob R, Gibson A. Used infant mattresses and sudden infant death syndrome in Scotland: case-control study. BMJ. 2002;325(7371): 1007–1012

Google ScholarCrossref PubMed

Arnestad M, Andersen M, Rognum TO. Is the use of dummy or carry-cot of importance for sudden infant death? Eur J Pediatr. 1997;156(12):968–970

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Mitchell EA, Taylor BJ, Ford RPK, et al. Dummies and the sudden infant death syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68(4):501–504

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Pollard K, et al. CESDI SUDI Research Team. Pacifier use and sudden infant death syndrome: results from the CESDI/SUDI case control study. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81(2):112–116

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

L’Hoir MP, Engelberts AC, van Well GTJ, et al. Dummy use, thumb sucking, mouth breathing and cot death. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158(11):896–901

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Li DK, Willinger M, Petitti DB, Odouli R, Liu L, Hoffman HJ. Use of a dummy (pacifier) during sleep and risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): population-based case-control study. BMJ. 2006;332(7532): 18–22

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Vennemann MM, Bajanowski T, Brinkmann B, Jorch G, Sauerland C, Mitchell EA; GeSID Study Group. Sleep environment risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome: the German Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):1162–1170

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Horne RS, Fyfe KL, Odoi A, Athukoralage A, Yiallourou SR, Wong FY. Dummy/pacifier use in preterm infants increases blood pressure and improves heart rate control. Pediatr Res. 2016;79(2):325–332

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Hauck FR, Omojokun OO, Siadaty MS. Do pacifiers reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome? A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):e716–e723

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Mitchell EA, Blair PS, L’Hoir MP. Should pacifiers be recommended to prevent sudden infant death syndrome? Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1755–1758

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Franco P, Scaillet S, Wermenbol V, Valente F, Groswasser J, Kahn A. The influence of a pacifier on infants’ arousals from sleep. J Pediatr. 2000;136(6):775–779

Google Scholar PubMed

Weiss PP, Kerbl R. The relatively short duration that a child retains a pacifier in the mouth during sleep: implications for sudden infant death syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160(1):60–70

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Tonkin SL, Lui D, McIntosh CG, Rowley S, Knight DB, Gunn AJ. Effect of pacifier use on mandibular position in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(10):1433–1436

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Avoid Smoke and Nicotine

Avoid smoke and nicotine exposure during pregnancy and after birth. Smoke in the infant’s environment after birth, and smoking by pregnant people are major risk factors for sleep related death.

-

Smoke exposure decreases and infants ability to arouse from sleep. It is estimated that ⅓ of all sleep-related infant deaths could be prevented if smoking was eliminated. The risk for sudden death doubles with even 1 cigarette per day, and increases predictably for every additional cigarette per day up to 20 cigarettes per day.

-

-

Tirosh E, Libon D, Bader D. The effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on sleep respiratory and arousal patterns in neonates. J Perinatol. 1996;16(6):435–438

Google Scholar PubMed

Franco P, Groswasser J, Hassid S, Lanquart JP, Scaillet S, Kahn A. Prenatal exposure to cigarette smoking is associated with a decrease in arousal in infants. J Pediatr. 1999;135(1):34–38

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Horne RS, Ferens D, Watts AM, et al. Effects of maternal tobacco smoking, sleeping position, and sleep state on arousal in healthy term infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;87(2):F100–F105

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Sawnani H, Jackson T, Murphy T, Beckerman R, Simakajornboon N. The effect of maternal smoking on respiratory and arousal patterns in preterm infants during sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(6):733–738

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Lewis KW, Bosque EM. Deficient hypoxia awakening response in infants of smoking mothers: possible relationship to sudden infant death syndrome. J Pediatr. 1995;127(5): 691–699

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Chang AB, Wilson SJ, Masters IB, et al. Altered arousal response in infants exposed to cigarette smoke. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(1):30–33

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Parslow PM, Cranage SM, Adamson TM, Harding R, Horne RS. Arousal and ventilatory responses to hypoxia in sleeping infants: effects of maternal smoking. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;140(1):77–87

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Anderson TM, Lavista Ferres JM, Ren SY, et al. Maternal smoking before and during pregnancy and the risk of sudden unexpected infant death. Pediatrics. 2019;143(4):e20183325

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Blair PS, Fleming PJ, Smith IJ, et al. Babies sleeping with parents: case-control study of factors influencing the risk of the sudden infant death syndrome. CESDI SUDI research group. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1457–1461

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Bacon C, et al; Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths Regional Coordinators and Researchers. Environment of infants during sleep and risk of the sudden infant death syndrome: results of 1993-5 case-control study for confidential inquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy. BMJ. 1996;313(7051): 191–195

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Vennemann MM, Hense HW, Bajanowski T, et al. Bed sharing and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome: can we resolve the debate? J Pediatr. 2012;160(1):44–8.e2

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Scragg R, Mitchell EA, Taylor BJ, et al; New Zealand Cot Death Study Group. Bed sharing, smoking, and alcohol in the sudden infant death syndrome. BMJ. 1993;307(6915): 1312–1318

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Blair PS, Sidebotham P, Pease A, Fleming PJ. Bed-sharing in the absence of hazardous circumstances: is there a risk of sudden infant death syndrome? an analysis from two case-control studies conducted in the UK. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107799

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Carpenter R, McGarvey C, Mitchell EA, et al. Bed sharing when parents do not smoke: is there a risk of SIDS? 7n individual level analysis of five major case-control studies. BMJ Open. 2013;3(5):e002299

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Arnestad M, Andersen M, Vege A, Rognum TO. Changes in the epidemiological pattern of sudden infant death syndrome in southeast Norway, 1984-1998: implications for future prevention and research. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85(2):108–115

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Zhang K, Wang X. Maternal smoking and increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta-analysis. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2013;15(3):115–121

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Avoid Alcohol and Drugs

Avoid alcohol, marijuana, opioids and illicit drug use both during pregnancy and after birth, as there is an increased risk of SIDS with prenatal and postnatal alcohol and drug use.

-

Studies are limited, but have shown increased risk of SIDS with use of cannabis, opioids (primarily methadone and heroin), cocaine, and alcohol.

-

Need help with substance use? SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

-

Alm B, Wennergren G, Norvenius G, et al. Caffeine and alcohol as risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome. Nordic Epidemiological SIDS Study. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81(2):107–111

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Williams SM, Mitchell EA, Taylor BJ. Are risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome different at night? Arch Dis Child. 2002;87(4):274–278

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Rajegowda BK, Kandall SR, Falciglia H. Sudden unexpected death in infants of narcotic-dependent mothers. Early Hum Dev. 1978;2(3):219–225

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Chavez CJ, Ostrea EM Jr, Stryker JC, Smialek Z. Sudden infant death syndrome among infants of drug-dependent mothers. J Pediatr. 1979;95(3):407–409

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Durand DJ, Espinoza AM, Nickerson BG. Association between prenatal cocaine exposure and sudden infant death syndrome. J Pediatr. 1990;117(6):909–911

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Ward SL, Bautista D, Chan L, et al. Sudden infant death syndrome in infants of substance-abusing mothers. J Pediatr. 1990;117(6):876–881

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Rosen TS, Johnson HL. Drug-addicted mothers, their infants, and SIDS. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;533:89–95

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Kandall SR, Gaines J, Habel L, Davidson G, Jessop D. Relationship of maternal substance abuse to subsequent sudden infant death syndrome in offspring. J Pediatr. 1993;123(1):120–126

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Avoid overheating and hats/head covering

Avoid overheating and hats and other forms of head covering.

-

It is unclear whether overheating is an independent risk factor for death, or if it reflects increased use of blankets/head covering and or sleeping on the stomach (not recommended).

One aerodynamics study of rebreathing showed that with higher temperature and higher humidity, the gas is denser and rebreathing is increased.

-

Overheating is associated with increased risk of sleep related death, but the definition of overheating is hard to pinpoint. A baby is considered overheated if the baby is sweating, has flushed skin or if the infant’s chest feels hot to the touch. A baby should be dressed appropriately for the environment with no more than 1 layer more than an adult would wear in the same situation. A baby is at higher risk of overheating if they sleep on the stomach (not recommended)

Be particularly careful about overheating on hot days, as a Canadian study found an almost 3-fold increase in SIDS on hot days vs. cooler days, though his finding was not found in other similar studies.

-

Fleming PJ, Gilbert R, Azaz Y, et al. Interaction between bedding and sleeping position in the sudden infant death syndrome: a population-based case-control study. BMJ. 1990;301(6743):85–89

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Ponsonby A-L, Dwyer T, Gibbons LE, Cochrane JA, Jones ME, McCall MJ. Thermal environment and sudden infant death syndrome: case-control study. BMJ. 1992;304(6822):277–282

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Ponsonby A-L, Dwyer T, Gibbons LE, Cochrane JA, Wang Y-G. Factors potentiating the risk of sudden infant death syndrome associated with the prone position. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(6):377–382

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Iyasu S, Randall LL, Welty TK, et al. Risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome among northern plains Indians. JAMA. 2002;288(21):2717–2723

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Ponsonby A-L, Dwyer T, Gibbons LE, Cochrane JA, Wang Y-G. Factors potentiating the risk of sudden infant death syndrome associated with the prone position. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(6): 377–382

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Auger N, Fraser WD, Smargiassi A, Kosatsky T. Ambient heat and sudden infant death: a case-crossover study spanning 30 years in Montreal, Canada. Environ Health Perspect. 2015; 123(7):712–716

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Waldhoer T, Heinzl H. Exploring the possible relationship between ambient heat and sudden infant death with data from Vienna, Austria. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184312

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Itzhak N, Greenblatt D. Aerodynamic factors affecting rebreathing in infants. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2019;126(4):952–964

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Obtain Regular Prenatal Care

Obtaining regular prenatal care is recommended to decrease the risk of sleep related death.

-

There is evidence linking a lower risk for SIDS in infants that have had regular prenatal care, but this may be complicated by other factors. People that are unable or unwilling to obtain regular prenatal care may be at higher risk of social, environmental or economic factors that may also be associated with increased risk of SIDS.

-

If you are having trouble finding prenatal care, reach out to your primary care physician or local clinic such as planned parenthood.

-

Getahun D, Amre D, Rhoads GG, Demissie K. Maternal and obstetric risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):646–652

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Kraus JF, Greenland S, Bulterys M. Risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome in the US Collaborative Perinatal Project. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(1):113–120

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Paris CA, Remler R, Daling JR. Risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome: changes associated with sleep position recommendations. J Pediatr. 2001;139(6):771–777

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Stewart AJ, Williams SM, Mitchell EA, Taylor BJ, Ford RP, Allen EM. Antenatal and intrapartum factors associated with sudden infant death syndrome in the New Zealand Cot Death Study. J Paediatr Child Health. 1995;31(5):473–478

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Immunize

Infants should be immunized in accordance with recommendations of the AAP and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Several large studies have found vaccines to be protective against SIDS.

There is no evidence that there is a causal relationship between immunization and SIDS. There is a decreased risk of SIDS immediately after vaccination, which might be linked to infants typically being healthy at the time of vaccination.

This is called the “Healthy vaccinee effect” (A recent illness places infants at higher risk for SIDS, and would be more likely to have delayed vaccines).

-

If you have questions about immunizations, talk to your child’s doctor, or check out these online resources. CHOP vaccine education center, the American Academy of Pediatrics or the Centers for Disease Control immunization site.

-

Mitchell EA, Stewart AW, Clements M. New Zealand Cot Death Study Group. Immunisation and the sudden infant death syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1995;73(6):498–501

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Jonville-Béra AP, Autret-Leca E, Barbeillon F, Paris-Llado J. French Reference Centers for SIDS. Sudden unexpected death in infants under 3 months of age and vaccination status–a case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51(3):271–276

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Platt MW, Tripp J, Smith IJ, Golding J. The UK accelerated immunisation programme and sudden unexpected death in infancy: case-control study. BMJ. 2001;322(7290):822

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Iqbal S, Shi J, Seib K, et al. Preparation for global introduction of inactivated poliovirus vaccine: safety evidence from the US Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, 2000–2012. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(10):1175–1182

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Virtanen M, Peltola H, Paunio M, Heinonen OP. Day-to-day reactogenicity and the healthy vaccinee effect of measles-mumps-rubella vaccination. Pediatrics. 2000;106(5):E62

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Avoid Unsafe Commercial Devices

At a minimum, any device used for sleep should meet the safety standards of the CPSC, the Juvenile product Manufacturers Association and the ATSM.

-

Many devices claim to reduce the risk of SIDS without evidence. The use of these products may lead to a false sense of security, or worse, relax a family’s adherence to safe sleep practices.

-

This includes recliners, many “sleepers” including the very popular “rock-n-play” and loungers such as the “doc-a-tot” which, unfortunately, are not safe sleeping surfaces. Wedges and sleep positioners are often made of soft materials and have been associated with cases of infant death. Also, falling asleep in a swing or carseat puts an infant at higher risk for SIDS and they should be moved to a safe sleep surface as soon as practical.

-

Avoid Home Monitors

Do not use home cardiorespiratory monitors as a strategy to reduce the risk of SIDS.

-

They just haven’t been shown to help, and maybe could decrease parental vigilance due to a false sense of security. A decision to use a home monitor is not a substitute for following safe sleep guidelines. Technology is constantly evolving and changing, so there certainly is the possibility that something may exist in the future that can help to prevent sudden death.

-

Like all parents, I was worried about SIDS and decided to use a monitor, we had a false alarm the first night we used it that brought us into urgent care just to make sure he was OK.

-

Tummy Time!

Supervised, awake tummy time is recommended to facilitate development and to minimize development of head flattening.

-

Tummy time really serves two purposes. Increasing the trunk strength could help a baby maintain a safe posture if they were to roll or move from their back. The second purpose of tummy time is to prevent the head flattening

-

Some babies don’t like tummy time. Propping the arms up under the collarbone can help them lift their head up, so they can enjoy tummy time a little easier.

Also, babies don’t have to be on the floor to count as tummy time. As long as they are awake, on their tummy and lifting their head, it counts. You can work up slowly to 30 minutes per day by 7 weeks of age.

-

Hutchison BL, Thompson JM, Mitchell EA. Determinants of nonsynostotic plagiocephaly: a case-control study. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):e316

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

To Swaddle or not to Swaddle…

There is no evidence to recommend swaddling as a strategy to reduce SIDS, but swaddling young infants (who have not shown signs of attempting to rol)l may be a reasonable option.

-

It is suggested that swaddling an infant correctly (snug around the chest, with ample room at the hips and knees) and placing an infant on their back may help prevent infants from rolling onto the stomach (not a recommended sleep position), and one study noted a decrease in the SIDS rate if infants are swaddled and placed on their back, BUT if the swaddled baby rolls to the stomach (not a recommended sleep position) the risk of SIDS skyrockets (12x).

-

If swaddling is used, the infant should be placed on their back. If a baby shows signs of attempting to roll (when awake or asleep), the swaddle should no longer be used. Weighted swaddles are not safe. If you choose to swaddle, watch out for any blankets becoming loose in bed and, as always also watch out for overheating.

-

Ponsonby A-L, Dwyer T, Gibbons LE, Cochrane JA, Wang Y-G. Factors potentiating the risk of sudden infant death syndrome associated with the prone position. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(6): 377–382

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Gerard CM, Harris KA, Thach BT. Physiologic studies on swaddling: an ancient child care practice, which may promote the supine position for infant sleep. J Pediatr. 2002;141(3):398–403

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

van Sleuwen BE, Engelberts AC, Boere-Boonekamp MM, Kuis W, Schulpen TW, L’Hoir MP. Swaddling: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e1097–e1106

Google Scholar Crossref PubMed

Join the Effort to Educate

I am also hoping to harness the power of our users to join in the effort educate parents, caretakers, leaders and media to encourage normalizing safe sleep practices in marketing materials, movies, and all forms of media. Together, we can save babies!